|

4.2 Deflection

There are three ways of deflecting risk:

-

Through insurance:

by which it is passed on to a

third party.

-

Through bonding:

by which a security is held against the risk.

-

Through the contract:

by which it is passed between

owner, contractor and subcontractors.

1.

Insurance:

A third party accepts an insurable risk for the payment

of a, premium, which reflects the impact of the risk and

the likelihood combined with the consequence.

2.

Bonding:

One or both parties to a contract deposit money into a

secure account so that if they or either party defaults,

the aggrieved party can take the bond in compensation.

This is a way of transferring the risk of one party

defaulting to that organization.

3.

Contract:

Through contracts the risk is shared

between owner contractor and subcontractors.

There are two common principles of

contracts:

a)

Risk is assigned to that pony most able

and best motivated to control it.

There is no point passing risk onto a

contractor or subcontractor if neither has the power or

the motivation to control it. The Institution of Civil

Engineers is currently revising its standard forms of

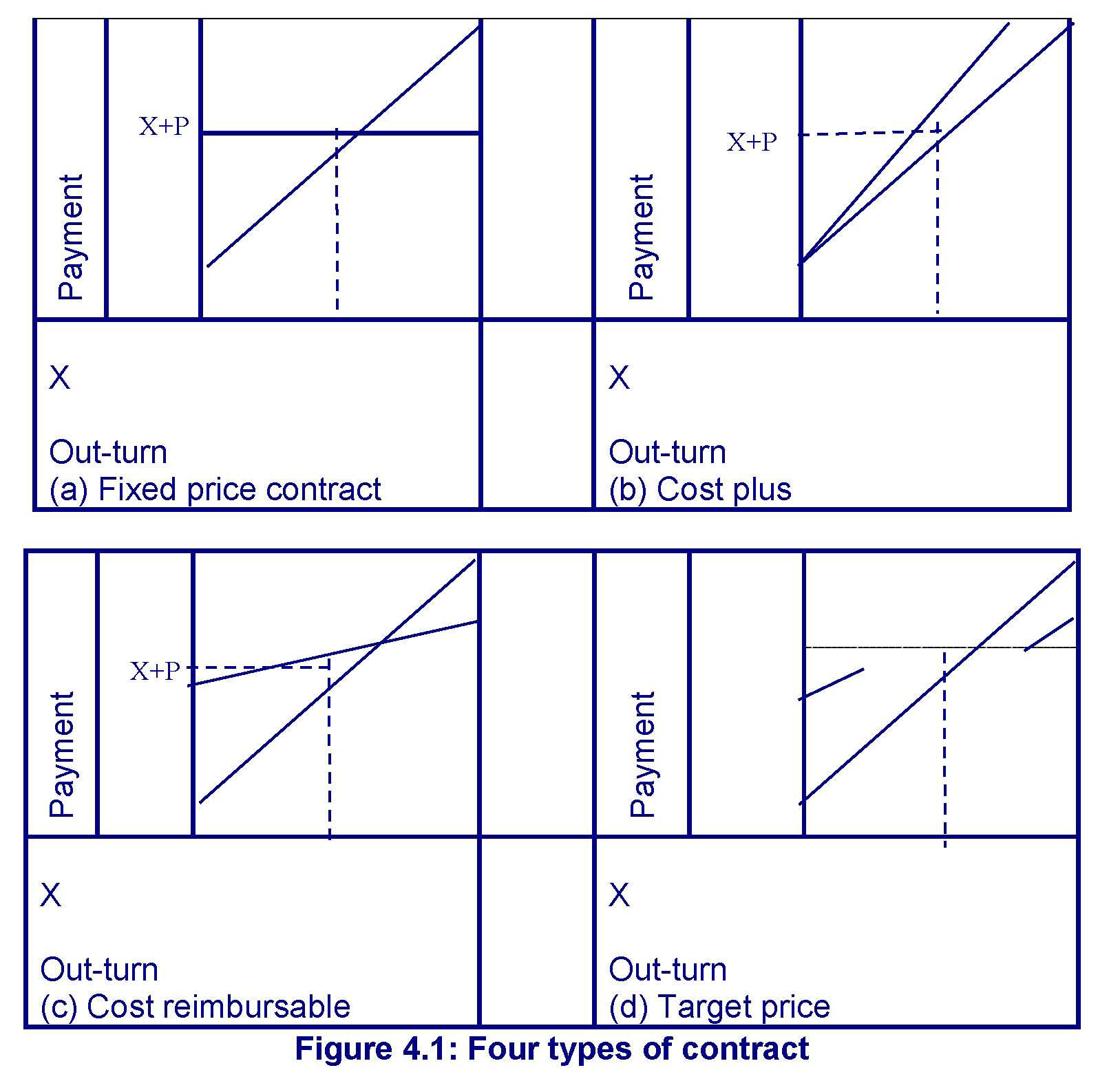

contract around this principle. There are four styles of

contract for different approaches to sharing risk:

-

Fixed price

-

Cost-plus

-

cost reimbursable

-

Target cost.

b)

Under fixed price contracts.

In Figure 4.1-a, the contractor accepts all the risk by

taking a fixed fee for the work regardless of how much

it costs. It is assumed that the owner has completely

specified the requirements and as long as they do not

change the contractor can meet a given price. This

approach is adopted for turnkey contracts, where the

contractor takes full responsibility and delivers to the

owner an operating facility. The owner has no role in

its construction. Often in fixed price contracts the

owner and contractor haggle over every change arguing

over which one of them caused it and whether it is

within the original specification.

When the owner cannot specify the

requirements,

the contractor should not accept the risk, but it

should be borne by the owner. The simplest way is

through cost-plus contracts, Figure 4.1-b. The

owner refunds all the contractor’s costs and pays a

percentage as profit. The disadvantage is that the

contractor is still responsible for controlling costs,

and yet the higher the costs the higher the profit. This

is a recipe for disaster as the party responsible for

control is not motivated to do it; in fact the exact

opposite. It is possible to adopt strict change control

and that passes responsibility for controlling costs

back to the owner, but can lead to strife. Typically,

cost-plus contracts are used on research contracts.

Another way of overcoming the problem

is to pay the contractor a fixed fee as a

percentage of the estimate, instead of a percentage of

the out-turn. This is a cost reimbursable contract.

Figure 4.1-c. The contractor can be motivated to

control costs if paid a bonus for finishing under

budget, or charged a penalty if over budget. However,

the parameters for the bonus or penalty must be

carefully set to ensure that the accepted risk is not

beyond the contractor’s control. Even without a bonus

the contractor may be motivated to control costs, as

that increases the percentage return.

Figure 4.1: Four types of contract

A related approach is target cost, Figure

4.1-d. The contractor is paid a fixed price, if the

out-turn is within a certain range typically

±

10 per cent of the budget. If the cost goes outside this

range, then the owner and contractor share the risk at

say 50p in the pound. If the costs exceed the upper

limit, the owner pays the contractor an extra 50p per

pound of overspend and if the price is below the range

the contractor reduces the price. This is often used on

development projects where there is some-idea of the

likely out-turn but it is not completely determined. The

contractor may also share in the benefits from the

product produced.

c)

Risk is shared with subcontractors if it

is within their sphere of control.

To achieve this, back-to-back contracts are used: the

clauses in the contract between owner and contractor are

included in that between contractor and subcontractors.

In some instances, where the contractor feels squashed

between two giants and accepts quite severe clauses from

the owner to win the work but believes that the

subcontractors will not accept them because they do not

need the work. This often happens to contractors on

defense or public sector projects. The way to avoid this

is to try to get the subcontractors to make their

contracts directly with the owner and use the owner's

power to pull the supplier into line. The supplier may

not need the business from the contractor but may have a

better respect for the owner.

|

Risk Assessment and

Risk Management(4)

Risk Assessment and

Risk Management(4)